At the root of the tension between shareholder and corporate interests is a classic conflict: maximising immediate financial returns for investors versus ensuring the long-term health and viability of the company itself. Under Dutch law, the lines are drawn quite clearly. Directors are legally bound to prioritise the broader corporate interest—a concept that encompasses not just shareholders but also employees, creditors, and long-term strategy—over the sometimes narrow, short-term profit motives of certain investors.

Understanding the Core Conflict in Dutch Corporate Governance

At the heart of many boardroom disputes lies a simple yet profound question: who does the company truly serve? Is it the shareholders who own its stock, or is it the enterprise itself, an entity with its own goals for continuity, innovation, and stability? This is one of the central conflicts defining modern corporate governance.

In many jurisdictions, particularly those following an Anglo-American model, the idea of shareholder primacy reigns supreme. This doctrine suggests that a company's main goal is to maximise wealth for its shareholders. The Netherlands, however, charts a different course, firmly embedding the stakeholder model into its legal fabric.

The Dutch Stakeholder Model

The Dutch approach, rooted in corporate law, requires a company's management to weigh the interests of all relevant stakeholders when making decisions. This means the needs of shareholders are considered right alongside those of others, such as:

- Employees: Safeguarding job security, fair wages, and a positive working environment.

- Creditors: Maintaining the company's financial health to honour its debts.

- Customers and Suppliers: Fostering sustainable, long-term business relationships.

- The Company Itself: Focusing on continuity and sustainable growth for the future.

This legal framework inherently creates the tension between shareholder and corporate interest. A decision that delivers a quick profit to shareholders might easily undermine the company's strategic goals for the long haul. For a deeper dive into how these principles are structured, you can learn more about the Dutch corporate governance framework in our detailed article.

Practical Examples of the Conflict

This theoretical conflict shows up in very real business decisions. Imagine a group of activist shareholders pushing for a large, one-time dividend payment to immediately boost their returns.

From a shareholder-first perspective, this makes perfect sense. However, the board of directors, guided by the Dutch stakeholder model, has to consider other factors. Would paying this dividend drain cash reserves needed for critical R&D? Could it lead to layoffs or put the company at risk during a future economic downturn?

Under Dutch law, the board’s duty is not to blindly follow shareholder demands but to act as a steward of the entire enterprise, balancing competing interests to secure a sustainable future. This responsibility is the cornerstone of our corporate legal system.

Investment is another common point of friction. A long-term investment in sustainable technology may not show immediate profits, which can frustrate shareholders focused on quarterly earnings. Yet, for the company's long-term survival and reputation, that same investment could be absolutely essential. The board must navigate these competing priorities, justifying decisions that serve the overarching corporate interest, even when they don't offer the quickest financial win for shareholders.

Defining Director Duties and Responsibilities in the Netherlands

To get to the heart of the tension between shareholder wants and corporate needs in the Netherlands, we first have to look at the legal duties placed on company directors. Unlike in more shareholder-focused systems, Dutch law doesn't see directors as simply agents for the shareholders. Instead, they act as stewards for the entire company.

A director’s core legal obligation, as laid out in the Dutch Civil Code, is to the corporate interest. This isn't a narrow concept. It covers the long-term health and continuity of the business, as well as the well-being of all its stakeholders. That means looking out for not just shareholders, but also employees, creditors, suppliers, and even the broader community the company operates in.

The Two Pillars of Director Duties

In day-to-day practice, this overarching responsibility is built on two key duties: the duty of care and the duty of loyalty. These principles are the compass for a director's decision-making and the standard by which Dutch courts will judge their actions when a conflict comes up.

-

The Duty of Care: This is about being diligent and sensible. Directors must act with the same level of care that any reasonably competent director would in a similar spot. It means staying informed, attending meetings, asking the tough questions, and making decisions based on solid information, not just a hunch.

-

The Duty of Loyalty: This duty is simple in theory but can be complex in practice. It demands that directors act in good faith, free from personal conflicts of interest. The company’s well-being must always come before their own personal gain or the interests of any outside party. This is absolutely central to managing the pull between shareholder and corporate interests.

Directors in the Netherlands carry a significant responsibility, guided by a broad duty to the company's long-term success. Grasping the fundamentals of what a fiduciary duty entails is a great starting point for understanding these obligations.

Navigating Conflicts of Interest

The duty of loyalty really comes into play when a director is also a major shareholder. In these situations, the potential for a clash between their personal financial interest as an owner and their duty to the company as a director is incredibly high.

Dutch law is very clear here: directors are required to disclose any potential or actual conflicts of interest to the board. Failing to do so can have serious consequences, including being held personally liable for any damages the company suffers because of a conflicted decision. Our detailed article on the role of the board of directors digs deeper into these governance structures.

This isn't just a box-ticking exercise. An undisclosed conflict of interest is a significant legal risk. Our firm has observed that such failures in governance can lead to costly proceedings at the Enterprise Chamber, potentially eroding significant market value and damaging corporate reputation. It’s a stark reminder of the real financial damage that happens when directors don't manage their dual roles correctly.

A director who is also a shareholder might be tempted to vote for a high-risk, high-reward strategy that could lead to a quick stock price increase but jeopardise the company's long-term stability. The duty of loyalty compels them to set aside their shareholder hat and act solely in the best interest of the corporation as a whole.

At the end of the day, the legal framework in the Netherlands is designed to make sure directors serve the entire enterprise. They must carefully balance competing demands, always guided by their duties of care and loyalty, to protect the company’s value and secure its future.

How Shareholders Can Exert Influence and Protect Their Interests

While Dutch law clearly tasks directors with safeguarding the company's long-term interests, that certainly doesn’t mean shareholders are left without a voice. Quite the opposite. The law provides a specific toolkit for shareholders to exert their influence and hold management accountable. Understanding these rights is crucial, both for investors wanting to protect their stake and for directors trying to maintain a constructive relationship with their company's owners.

These mechanisms aren't there to let shareholders run the company day-to-day. Instead, they create a balance of power, giving them formal, structured ways to question or challenge the board’s direction.

Key Shareholder Rights Under Dutch Law

Shareholders are not meant to be passive observers; they have distinct legal rights to make themselves heard. The main stage for this is the general meeting of shareholders, which remains the ultimate decision-making body for certain fundamental corporate matters.

Key rights include:

- The Right to Call a General Meeting: If shareholders holding a certain percentage of the company's capital feel an issue is urgent, they can force the board to call a general meeting. This is a powerful way to bring critical matters to the forefront outside of the usual annual schedule.

- The Right to Add Items to the Agenda: In a similar vein, shareholders who meet a specific ownership threshold can add items to the agenda of an upcoming meeting. This guarantees that their specific concerns—whether about company strategy, executive pay, or a proposed merger—get a formal discussion.

- The Right to Ask Questions: During any general meeting, every single shareholder has the fundamental right to question the board of directors on company policy and performance. This is a real cornerstone of corporate transparency and accountability.

These aren't just symbolic gestures. They offer a legally recognised path for shareholders to engage directly with the board and influence corporate policy. Of course, exercising them means meeting specific criteria, which can vary depending on what’s written in the company’s articles of association.

Escalating Disputes to the Enterprise Chamber

What happens when dialogue breaks down and general meetings fail to resolve a deep-seated conflict? Shareholders have a much more formidable option. In the Netherlands, this is when serious disputes often land in the Enterprise Chamber of the Amsterdam Court of Appeal—a specialist court designed to handle exactly these kinds of complex corporate governance fights. This is where the tension between shareholder and corporate interest is frequently tested.

A key tool here is the "inquiry proceeding" (enquêteprocedure). This can be initiated by shareholders who meet certain capital thresholds, typically requiring a significant stake (though this can often be met by a group of shareholders banding together). An inquiry proceeding essentially asks the court to appoint investigators to scrutinise the company's management and policies. For a deeper dive into this area, you can find excellent insights on shareholder rights and activism in the Netherlands.

If the Enterprise Chamber finds evidence of mismanagement, it has sweeping powers to intervene directly. It can suspend directors, cancel board decisions, or even temporarily appoint new board members to get the company back on track.

This judicial oversight acts as a vital check on corporate power. It ensures that boards can't simply ignore legitimate shareholder concerns forever. For shareholders who feel the board is failing in its duty, it’s the ultimate backstop.

The Double-Edged Sword of Shareholder Activism

While these tools are essential for good governance, they can also be wielded to push for short-term gains that might not align with the company's long-term health. This brings us to the core challenge of shareholder activism.

An activist investor might use their rights to demand aggressive cost-cutting, a quick sale of the company, or a huge dividend payout. All of these moves could boost the share price right now but potentially cripple the company's ability to innovate and grow down the road. For directors, this creates an incredibly difficult balancing act: they have to respect shareholder rights while staying true to their legal duty to protect the long-term vitality of the entire enterprise.

To navigate this complex terrain, it helps to see the tools available to both sides.

Shareholder Rights vs Corporate Defense Mechanisms

Here's a look at how the tools shareholders can use to influence policy are often countered by measures companies employ to maintain stability and focus on long-term strategy.

| Shareholder Tool | Objective | Typical Corporate Response / Defence |

|---|---|---|

| Calling a General Meeting | Force a discussion on an urgent issue (e.g., a hostile takeover bid). | Use of protective foundations (stichtingen) or issuance of preference shares to dilute voting power. |

| Agenda Placement | Push for strategic changes, like a spin-off or sale of an asset. | The board can argue the proposal conflicts with the long-term corporate interest. |

| Voting Against Proposals | Block board-backed initiatives, such as executive remuneration plans. | Engage in proactive shareholder communication to win support before the meeting. |

| Initiating Inquiry Proceedings | Seek judicial intervention based on claims of mismanagement. | Demonstrate that board decisions were made reasonably and in the corporate interest. |

Understanding this dynamic is key. The relationship isn't always adversarial, but knowing the levers each side can pull helps explain why corporate governance disputes can become so intense.

Using Corporate Defence Mechanisms to Safeguard Company Interests

When shareholder activism starts to look like it might derail a company's long-term strategy, Dutch law provides a well-established set of tools to defend the corporate interest. These mechanisms aren’t designed to entrench management forever. Instead, they’re there to create stability, fend off hostile takeovers, and give the board the breathing room it needs to pursue sustainable growth.

For international investors, getting to grips with these protective layers is crucial, as they can significantly shift the balance of power within a company. These aren't just obscure legal technicalities; they are active, powerful instruments that genuinely shape corporate control in the Netherlands.

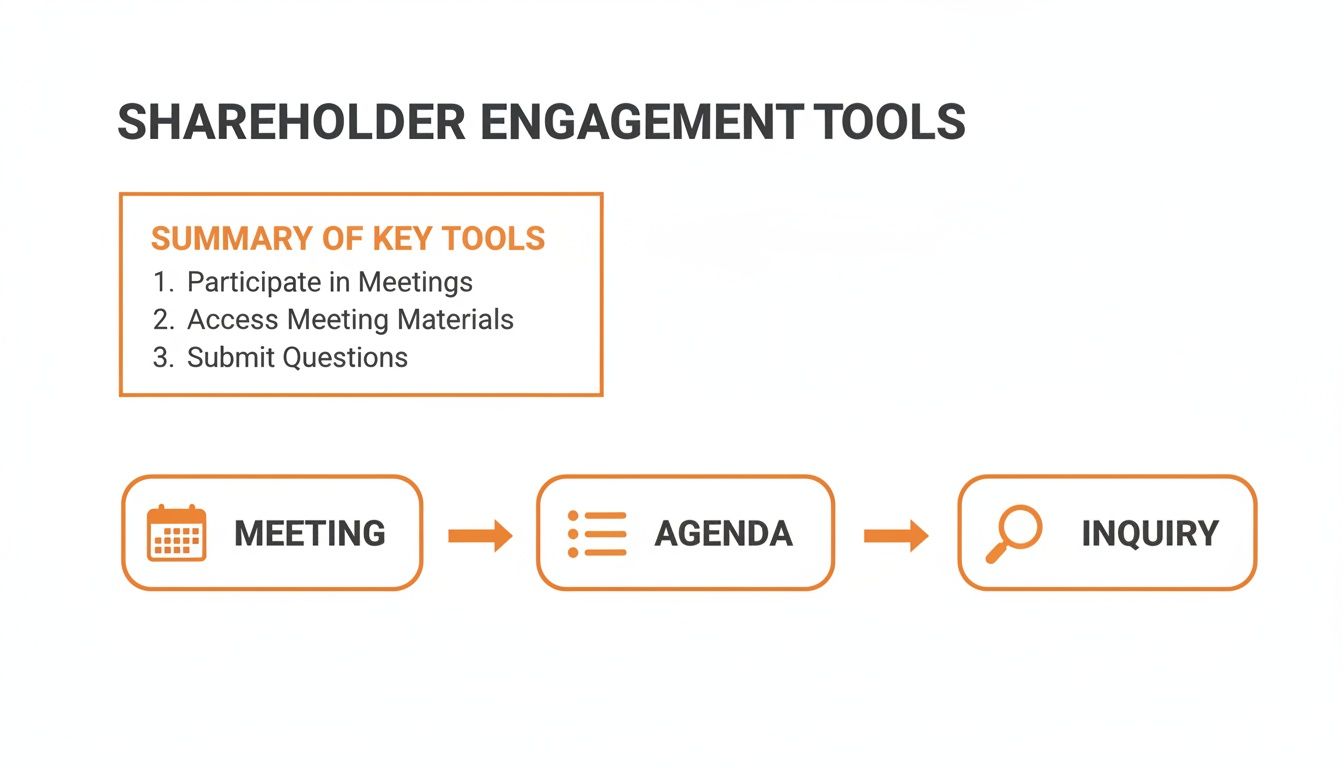

This diagram offers a quick look at the main ways shareholders can engage with a company—actions that often trigger the need for these defensive strategies in the first place.

As you can see, the graphic highlights fundamental shareholder rights—like calling meetings, setting agendas, and launching inquiries. These are the primary channels shareholders use to challenge a board’s direction.

Common Protective Measures in Dutch Companies

Dutch corporate law allows for several types of defence mechanisms. Each serves a slightly different purpose, but they all aim to protect the company from unwanted external influence.

Here are the key examples:

-

Priority Shares (Prioriteitsaandelen): These are special classes of shares that grant their holders specific control rights, such as the power to nominate or approve board members. Often, they are held by the company's founders or a dedicated foundation, effectively giving a small, stable group a major say in key governance decisions.

-

Protective Foundations (Stichtingen): A very common Dutch defence involves a friendly foundation (stichting administratiekantoor, or STAK). This foundation holds the shares and then issues depositary receipts to the public. While the receipt holders get the economic benefits of the shares, the voting rights stay with the foundation's board, which is expected to act in the company's best interest.

-

Issuing Preference Shares: A company can grant a friendly foundation the option to acquire a large block of preference shares. If a hostile takeover kicks off, the foundation can exercise this option, effectively watering down the acquirer's stake and voting power to stop them from gaining control.

These tools are powerful, no doubt, but their use is not unlimited. A critical legal principle keeps them in check.

The Principle of Proportionality

Dutch courts simply will not allow a board to use these defences in a way that is excessive or permanently blocks legitimate shareholder influence. The principle of proportionality is absolutely key here.

Any defensive measure taken must be a reasonable and temporary response to a specific, identifiable threat to the corporate interest. It cannot be used to create a fortress that makes the board entirely unaccountable to its shareholders.

What this means in practice is that a defence mechanism should be reversible and shouldn't disproportionately harm shareholder rights. For instance, issuing preference shares to block a hostile bid is generally seen as acceptable, but only for a limited time to allow the board to negotiate or find a better alternative.

Loyalty Voting Schemes: A Contentious Frontier

Another mechanism, loyalty voting, rewards long-term shareholders with extra voting rights. As you might imagine, these can create significant friction. Loyalty share schemes in Dutch companies really highlight the tension between entrenched corporate control and the rights of minority shareholders, and have been the subject of important court rulings.

For example, a court might block a loyalty voting structure if it is deemed to unreasonably prejudice a significant minority shareholder by solidifying absolute control for another, effectively silencing any dissenting voices. You can explore a full analysis of loyalty schemes in the Netherlands for more detail on this complex area.

This demonstrates the court's role in policing the boundaries of defensive tactics, ensuring they serve the corporate interest without unfairly trampling on shareholder rights.

Resolving Disputes Through the Enterprise Chamber and Mediation

When dialogue between a company’s board and its shareholders collapses, things can escalate quickly. Defensive mechanisms might fail to restore balance, and before you know it, a dispute has turned into a full-blown legal battle. In the Netherlands, the main arena for these high-stakes corporate conflicts is a specialised court: the Enterprise Chamber (Ondernemingskamer) of the Amsterdam Court of Appeal.

This isn't your typical courtroom. It's purpose-built to handle complex corporate disputes where the tension between shareholder and corporate interest has reached a boiling point. Its core function is to investigate and provide swift, decisive resolutions when there are well-founded reasons to doubt the correctness of a company's policy.

The Unique Power of the Enterprise Chamber

The Enterprise Chamber's most powerful tool is the inquiry proceeding (enquêteprocedure). As we've touched on, shareholders who meet certain capital thresholds can petition the court to launch an investigation into a company’s management and its affairs.

If the court agrees there are sufficient grounds for an inquiry, it gets to work, appointing independent experts to conduct a thorough review. This process alone can bring some much-needed clarity to a murky situation.

But the Chamber's real teeth are in its ability to impose immediate, far-reaching provisional measures while the investigation is still ongoing. These aren’t just suggestions; they are binding orders designed to stabilise the company and prevent any further damage.

The Enterprise Chamber can act decisively to protect the corporate interest. It has the authority to suspend directors, annul specific board resolutions, or even appoint a temporary director or supervisor to oversee the company’s management.

These powers make the Chamber a formidable venue for shareholders who feel mismanagement is destroying their investment. For directors, the mere prospect of such an intervention is a powerful incentive to ensure their decisions are well-reasoned, transparent, and clearly aligned with the company’s long-term interests. For a detailed look at this process, you can explore our guide on an inquiry procedure at the Enterprise Chamber.

Beyond the Courtroom: Mediation and Settlement

While the Enterprise Chamber offers a definitive legal path, going to court isn’t always the best answer. Litigation can be incredibly costly, drag on for months or years, and inflict lasting damage on crucial business relationships. This is particularly true for small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and startups, where a protracted legal fight can drain the very resources needed for survival.

Recognising this reality, there's a growing emphasis on alternative ways to resolve disputes, like mediation.

Mediation provides a confidential and more collaborative setting where shareholders and directors can work through their differences with the help of a neutral third party. The goal isn't to declare a winner but to find a mutually acceptable path forward that preserves the company’s value and ensures its continuity.

The benefits of mediation in these situations are clear:

- Cost-Effectiveness: Mediation is almost always far less expensive than a full inquiry proceeding.

- Speed: A resolution can often be reached in a matter of weeks, not the months or years a court case can take.

- Confidentiality: Unlike public court proceedings, mediation keeps sensitive business matters private and out of the public eye.

- Relationship Preservation: By fostering genuine dialogue, mediation can help repair trust and allow the parties to find a way to continue working together.

Even when a case is already before the Enterprise Chamber, the judges themselves frequently encourage the parties to try and reach a settlement. After all, a negotiated outcome that everyone can agree to is often far better than a decision imposed by the court, as it allows for more creative and tailored solutions that truly fit the company's specific needs.

Practical Strategies for Balancing Shareholder and Corporate Interests

Getting the balance right between shareholder expectations and the company's long-term health is more art than science. It goes far beyond simply knowing the law; it requires practical, forward-thinking strategies from everyone involved. Both directors and shareholders have a part to play in creating a governance structure that champions long-term value without sidelining the investors who back the company.

By putting clear frameworks and communication channels in place, what might otherwise become a conflict can instead be a constructive conversation. A proactive approach here can save a world of trouble—and legal fees—down the line.

Guidance for Directors

For directors, the name of the game is building a resilient governance framework that allows you to make strategic decisions and justify them with complete clarity. This isn't just about ticking compliance boxes. It's about weaving transparency and genuine stakeholder engagement into the very fabric of the company.

Here are a few key actions directors should be taking:

- Establish a Clear Strategic Vision: You need a long-term plan that you can communicate consistently. This plan should clearly connect today's decisions, like reinvesting profits, to tomorrow's sustainable growth.

- Maintain Robust Documentation: Keep meticulous records of board discussions, especially when making tough calls. This paperwork should show precisely how the board considered the interests of different stakeholders and why it landed on a particular path as being in the company's best interest.

- Foster Open Shareholder Communication: Don't just wait for the annual meeting to talk to your investors. Regular updates, open forums, and proactive outreach build trust and help manage expectations before they become demands.

Guidance for Shareholders

Shareholders, on the other hand, can't afford to be passive. Protecting your investment means more than just watching the share price. It means you need to be an informed and engaged participant, understanding the company’s rules and knowing exactly how and when to use your rights. The push-and-pull between short-term returns and long-term corporate stability often comes into sharp focus during corporate decisions regarding stock buybacks versus dividends.

To be effective, shareholders should consider these steps:

- Conduct Thorough Due Diligence: Before you even invest, dig into the company’s articles of association and governance policies. Be on the lookout for things like anti-takeover measures or unique share structures that could water down your influence.

- Exercise Your Rights Constructively: Your rights—like asking questions at general meetings or adding items to the agenda—are powerful tools. Use them to get clarity and hold the board accountable, not just to agitate for a quick payout.

- Know When to Collaborate: If you have serious concerns, a lone voice is easily ignored. Consider teaming up with other shareholders to meet the capital thresholds needed for more significant actions, like requesting a formal inquiry. There's strength in numbers.

Frequently Asked Questions

It’s one thing to understand the theory of corporate governance, but it’s another thing entirely to deal with it in the real world. When the goals of shareholders and the company’s long-term health don’t quite line up, directors and investors are often left with pressing questions. Here are our answers to a few common scenarios we see in our practice, grounded in the realities of Dutch corporate law.

What Should a Director's First Step Be When Shareholder Demands Conflict with a Long-Term Plan?

Your first move should always be to document everything meticulously and seek legal advice. Imagine a shareholder group is pushing hard for a huge dividend payout, but that cash is earmarked for a crucial factory upgrade outlined in your company's approved strategic plan. In this situation, a director’s duty under Dutch law is clear: you must prioritise the corporate interest.

This means you need to formally record the shareholder’s demand and then prepare a detailed, evidence-based response explaining why sticking to the long-term plan is better for the company as a whole. Pull together your financial projections, market analysis, and the risks of not making that investment. While you should maintain open communication with the shareholder, your legal obligation is to the company's future, not one shareholder's short-term gain.

How Can Minority Shareholders Challenge a Majority Decision That Harms the Company?

Minority shareholders are certainly not without options. Let's say a majority shareholder forces through a sale of a key company asset to a related party for a suspiciously low price. This is a classic example of a decision that could seriously damage the company’s long-term value.

The most powerful tool available to minority shareholders is to start an inquiry proceeding at the Enterprise Chamber in Amsterdam. If they can gather enough support to meet the capital threshold—which varies but is substantial—they can petition the court to investigate the company for mismanagement. The court can order immediate remedies, like suspending the damaging decision, which is a potent way to protect both their investment and the company itself from a self-serving majority.

How Can a Shareholders' Agreement Prevent Profit Distribution Disputes?

A well-drafted shareholders' agreement is your best form of defence; it's proactive, not reactive. These agreements can lay out a clear, agreed-upon policy for how profits are distributed, stopping future fights before they even start.

For example, you could include a clause stating that a specific percentage of profits must be reinvested for the first five years of operation. Or perhaps dividends will only be paid out once the company hits certain revenue targets.

By contractually defining the rules around dividends and reinvestment from the outset, a shareholders' agreement transforms a potential point of conflict into a settled matter of company policy. This provides certainty for all parties and aligns shareholder expectations with the company's strategic growth objectives.

This kind of forward-thinking is particularly crucial for startups and SMEs, where getting every stakeholder on the same page about the long-term vision isn't just helpful—it's essential for survival.

At Law & More, our corporate law specialists provide expert guidance on navigating the complex duties of directors and the rights of shareholders. Whether you are drafting a robust shareholders' agreement or responding to a dispute, we offer pragmatic solutions to protect your interests and ensure corporate stability. Contact us to find out how we can help at https://lawandmore.eu.